This webpage was created for a poster presentation at the GRACE symposium on 09/07/22

Greetings

Hello, if you are here from the poster presentation, welcome to my website. My name is Santosh, and I am a third-year ChemE Ph.D. at UF (Fig.1a).

who does know where the camera is.

You’ve probably (hopefully) met my undergrad, Grace Shoemaker (Fig. 1b), who probably (hopefully) tried to explain to you our research project affectionately named SAHARA (not the desert).

So, Why am I here?

You are here because we thought a mere poster was not sufficient to do justice to the depth of our work. Posters can be confusing, especially if the topic of the poster is outside your area of expertise (Fig.2a).

(Source: PhD comics)

From previous experience, we noticed that a majority of the people stopping by would just stare at the poster blankly for 5-10 min, nod their heads, and then move on politely, without really grasping the true meaning of our work.

So this time, we decided to bring all the fundamental information directly to you (dear reader), long after you have already nodded your head and moved on. We are doing this in the hope that this will help our work reach a wider audience.

So, what is this SAHARA you keep talking about?

First, a little backstory.

CRISPR/Cas systems

In our lab, we work primarily on discovering and engineering novel CRISPR/Cas systems1 for genome editing and molecular diagnostic applications.

If you haven’t come across CRISPR before and would like to learn more, I have written an introductory article here.

If you are too lazy to read all that, just know the following:

- CRISPR stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats.

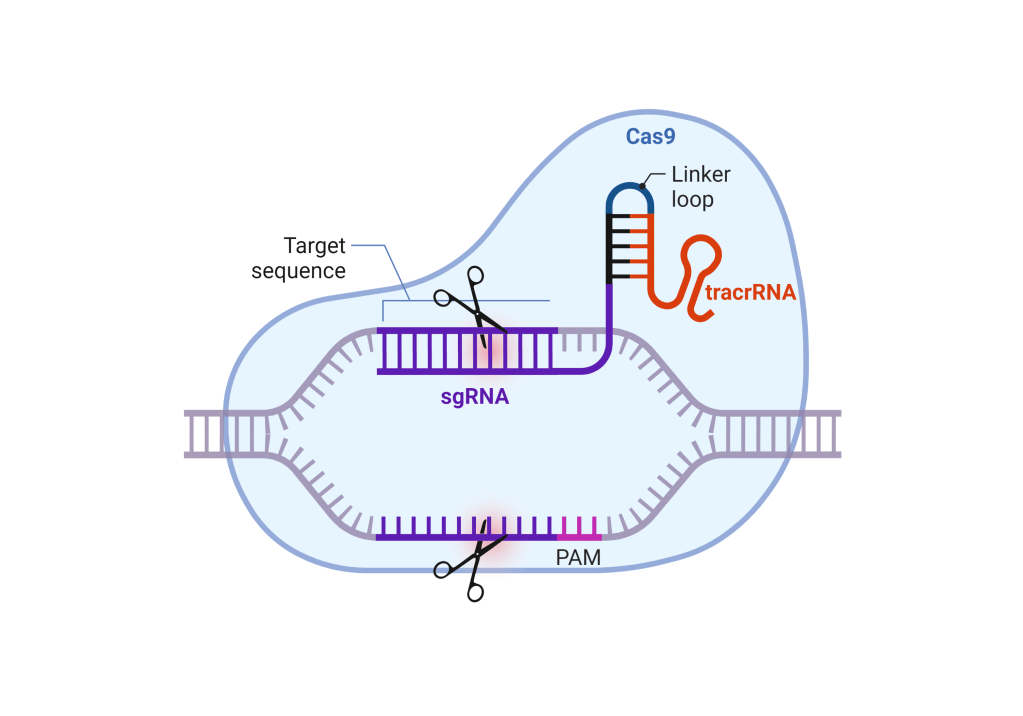

- It is essentially a defense mechanism found in prokaryotic cells such as bacteria and archaea, that is made of two things: an enzyme called Cas and a short piece of RNA most commonly known as the guide RNA or the sgRNA. The Cas and the guide often come together to form a binary complex. This complex then binds and cuts any DNA that is complementary to the sgRNA in a targeted fashion (Fig. 3a).

- The cool thing about CRISPR-Cas systems is that they can be repurposed to cut any sequence of DNA by merely changing the sequence of the sgRNA, thus earning them the moniker of ‘molecular scissors’.

CRISPR Diagnostics

There are many different types of Cas proteins2. The most famous one and the first one to be discovered is Cas9.

However, a few years ago two new classes of Cas enzymes with a very unique property were discovered. These new Cas enzymes were called Cas123 and Cas134, respectively, and were classified into the type V and type VI sub-groups.

Cas12 was discovered to cut DNA (just like Cas9), while Cas13 was found to cut RNA. Unlike other Cas proteins, however, these new Cas proteins had this unique property called trans-cleavage.

Essentially, after making sgRNA driven targeted cuts in the DNA (or RNA) these Cas enzymes were found to go crazy and cut any ssDNA (Cas12) or ssRNA (Cas13) sequences that were hovering around in their vicinity.

This new property was sort of unique and weird, but researchers soon realized that they can actually harness this property to develop powerful diagnostic platforms by making these enzymes cut fluorescent reporters in the presence of pathogenic DNA or RNA (Fig. 3b) thus enabling quick and easy detection of any pathogen.

CRISPR-based diagnostics took off as soon as it was discovered due to its simplicity, affordability, and portable nature. They overcame a lot of the limitations displayed by contemporary techniques such as RT-qPCR.

Very quickly CRISPR-based tests were developed for a range of clinical targets such as Malaria, HCV, HIV, as well as COVID-19, among others. Our own lab developed two different types of CRISPR-based for the detection of COVID in the middle of the pandemic5,6.

You still haven’t told me what SAHARA is

Yes we know, we are building up to it.

SAHARA

We described earlier that Cas12 can only detect DNA. However, not all pathogens are made of DNA. Many viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, are RNA viruses and do not have any DNA sequence within them. In order to detect such RNA sequences with Cas12, a reverse-transcription step needs to be employed to first convert all the RNA to DNA and then perform CRISPR-based detection. This is inconvenient because it adds to the time, cost, and complexity of the assay.

The alternative is to use an RNA-detecting enzyme such as Cas13, but then you have to switch enzymes every time you switch the target between DNA and RNA. Wouldn’t it be super-convenient if you can detect both DNA and RNA with a single enzyme?

This is what SAHARA is all about.

In this project, we found a way to make Cas12a detect RNA as well as DNA directly without any additional steps such as reverse transcription or strand displacement.

Cool, but how?

Truth is, we made this discovery quite accidentally.

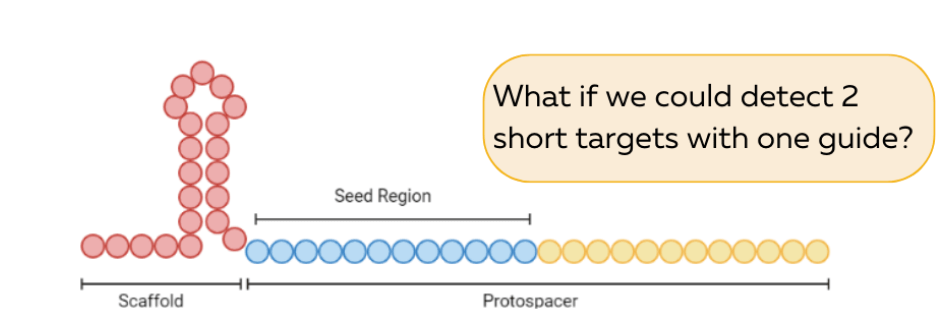

To understand it, you need to know that the guide RNA for Cas12a is typically 42-nt long and is made up of a scaffold (Fig.4a red) that acts as a handle for Cas12a to bind and a protospacer (Fig.4a blue and yellow) that recognizes and binds to the target DNA that needs to be cleaved.

(blue+yellow)

You will notice that we have displayed the protospacer in two different colors – blue and yellow. It is known in our field that the first few nucleotides of the protospacer that are closer to the handle (the blue region) are more important for Cas12-mediated cleavage. Mismatches between the guide and the target at these positions are often not tolerated by Cas12a at all and in many cases lead to a lower cleaving efficiency. Due to its importance, this region is known as the ‘seed’ region.

The yellow part of the protospacer, on the other hand, seems to be less strict in its binding capabilities, often allowing mismatches along these positions to also be efficiently cleaved.

Turns out, when we were tinkering with short targets that each distinctly bind specifically to the blue or the yellow, we found that only the blue region of the protospacer has a strict preference for a DNA target, while the yellow was able to tolerate both DNA as well as RNA for initiating cleavage.

This was extremely surprising to us at first, because we were not expecting any RNA cleaving ability from Cas12a at all. However, the implication of our discovery meant that we could theoretically detect any RNA sequence at the yellow part of the guide provided we also supply a synthetic DNA to bind to the blue ‘seed’ region. We call this the ‘split-activator’ approach for detection because we are splitting the guide RNA to bind partially to a synthetic DNA target and partially to RNA.

We called this method S.A.H.A.R.A. It is short for Split Activators for Highly Accessible RNA Analysis. With SAHARA we were able to detect picomolar levels of HCV RNA as well as a short microRNA (mRNA-155) without any pre-amplification or reverse-transcription. This is important because normally Cas12a cannot detect RNA at all, no matter how high the concentration.

We are still working to understand the exact mechanism that enables SAHARA. While we know it can detect RNA, we still do not fully understand how it is able to do it. Hopefully, in time, we will solve that mystery as well.

Thank you for reading.

– Santosh and Grace

References

- Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012 Aug 17;337(6096):816-21. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. Epub 2012 Jun 28. PMID: 22745249; PMCID: PMC6286148.

- Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Iranzo J, Shmakov SA, Alkhnbashi OS, Brouns SJJ, Charpentier E, Cheng D, Haft DH, Horvath P, Moineau S, Mojica FJM, Scott D, Shah SA, Siksnys V, Terns MP, Venclovas Č, White MF, Yakunin AF, Yan W, Zhang F, Garrett RA, Backofen R, van der Oost J, Barrangou R, Koonin EV. Evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020 Feb;18(2):67-83. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0299-x. Epub 2019 Dec 19. PMID: 31857715; PMCID: PMC8905525.

- Zetsche B, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Slaymaker IM, Makarova KS, Essletzbichler P, Volz SE, Joung J, van der Oost J, Regev A, Koonin EV, Zhang F. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 2015 Oct 22;163(3):759-71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038. Epub 2015 Sep 25. PMID: 26422227; PMCID: PMC4638220.

- Kellner MJ, Koob JG, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, Zhang F. SHERLOCK: nucleic acid detection with CRISPR nucleases. Nat Protoc. 2019 Oct;14(10):2986-3012. doi: 10.1038/s41596-019-0210-2. Epub 2019 Sep 23. Erratum in: Nat Protoc. 2020 Mar;15(3):1311. PMID: 31548639; PMCID: PMC6956564.

- Nguyen LT, Rananaware SR, Pizzano BLM, Stone BT, Jain PK. Clinical validation of engineered CRISPR/Cas12a for rapid SARS-CoV-2 detection. Commun Med (Lond). 2022 Jan 12;2:7. doi: 10.1038/s43856-021-00066-4. PMID: 35603267; PMCID: PMC9053293.

- Nguyen LT, Macaluso NC, Pizzano BLM, Cash MN, Spacek J, Karasek J, Dinglasan RR, Salemi M, Jain PK. A Thermostable Cas12b from Brevibacillus Leverages One-pot Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2021 Oct 18:2021.10.15.21265066. doi: 10.1101/2021.10.15.21265066. Update in: EBioMedicine. 2022 Mar;77:103926. PMID: 34704101; PMCID: PMC8547533.